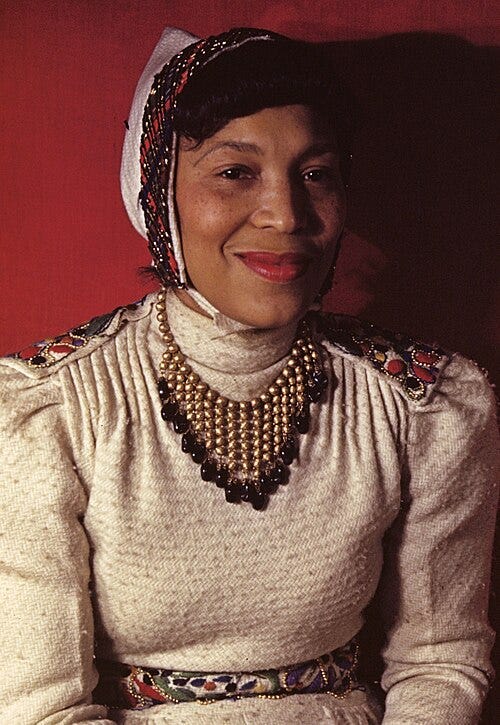

If you’re into literature, you’ve probably heard of Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960) (and if you hadn’t before, now you have). She’s a classic author of American literature, especially African American literature. But writing literature didn’t seem to be her first plan. While putting herself through college, she’d published some short stories, a play, and started a college newspaper, The Hilltop. But it was anthropology she was studying, not literature. She came up with early giants of the discipline at Columbia University, including Ruth Benedict, Margaret Mead, and Franz Boaz (often credited as creating the field of cultural anthropology).

This was at a time when many anthropologists insisted on travelling out there – to far-flung places. But Hurston wanted to study the folklore and culture of African Americans in the US South, where she was from. She wanted to do insider anthropology. While at Columbia she lived in Harlem, where she met African American authors of the Harlem Renaissance. This movement had been growing over the years, producing art, music and literature that fundamentally challenged stereotypes about African Americans during the time of Jim Crow South.

Hurston found it difficult to make it as an anthropologist at the time (thanks to inherent racism and sexism). But rather than let herself be curtailed, she chose to merge her two passions of literature and anthropology and create something wholly different. To her colleague Countee Cullen, a poet of the Harlem Renaissance, she wrote:

I have the nerve to walk my own way, however hard, in my search for reality, rather than climb upon the rattling wagon of wishful illusions.

What reality was she seeking, through fictions?

Her blending of ethnography and fiction was considered suspect at the time,1 cementing her difficulties in finding work in the academe. Neither was Hurston considered a greatly successful author during her lifetime. Some African American literary scholars and critics thought she wasn’t politically motivated enough while anthropologists didn’t think her work was reliable or objective enough.

She beat her own path, but this path was only widely recognised for its importance after her death. One of her key contributions – both to literature and anthropology – is the ethnographic novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God.

Their Eyes Were Watching God

Hurston's second novel, Their Eyes was released in 1937, two years after her autoethnographic folklore collection, Mules and Men (1935) and three years after her first novel, Jonah's Gourd Vine (1934). Their Eyes follows the life of Janie, from West Florida, and her three marriages.

Here’s a brief summary of the plot (spoilers):

As a sixteen-year-old, Janie's grandmother arranges for Janie to marry Logan, a local landowner. Initially resistant, Janie eventually agrees. But the marriage quickly soures as Logan attempts to control her independent spirit, ultimately threatening her life.

When Janie meets the charming and successful Jody Starks, she abandons Logan to follow him to Eatonville, the first town formally established by African Americans. When they arrive, Jody uses his wealth to buy property, open a shop, and position himself as a community leader. Though rarely physically violent, Jody controls Janie by silencing her and confining her to the shop. His stubbornness eventually gets him killed, though, and Janie is left a wealthy widower.

Numerous suitors come calling for Janey’s hand, but she isn’t interested in any of them. Not until Tea Cake starts turning up at the store. A younger man with a less than stellar reputation, Tea Cake is handsome and charming, and seems enamoured with Janie. Everyone warns her he isn’t the type to be trusted, but despite her early doubts Janie soon agrees to leave Eatonville and build a life with him.

What follows is love, hardship, and a devastating cyclone.

Ethnographic Fiction

What makes Their Eyes work so remarkable is how Hurston seamlessly blends ethnographic observation, personal experience, and powerful storytelling. Their Eyes isn't just a love story — it's an anthropological document hidden in a richly evoked story of hardship and perseverance capturing the lived experiences, language patterns, and cultural practices of Black communities in the American South during the early 20th century. Hurston wrote what we now call ethnographic fiction, a genre that uses creative narrative and fiction to convey cultural truths. The narrative explores social structures and gender dynamics in ways that academic text could not reflect.

When Jody forbids Janie from speaking at public gatherings, he's enacting a form of silencing that Hurston observed in her fieldwork: "Mah wife don't know nothin' 'bout no speech-makin'," Jody proclaims, prompting Janie to wonder if maybe she does have a thing or two worth saying now and then.

Self-determination is a central theme in the book, but so too is the voice of African Americans. Hurston conveys much of the story through "porch talks", a form of engagement that is quintessentially American.2 The porch is a liminal space between the home and wider civic and cultural world, where people come together, talk, joke, and perform. In Their Eyes the "lying sessions" on the porch are a chance for people to tell tall tales and, as an anthropologist, Hurston recognised these exchanges as vital cultural practices that preserved history and reinforced community bonds.

Dialogue also becomes a means of cultural preservation in Their Eyes. Hurston insisted on writing it in an authentic vernacular of people she knew best. This choice, criticised at the time for reinforcing negative stereotypes, was a means of preserving linguistic patterns that carried cultural significance and history. As an example, in the final pages Janie explains her feelings for Tea Cake:

Love is lak de sea. It’s uh movin’ thing, but still and all, it takes its shape from de shore it meets, and it’s different with every shore.

I can’t read this line without hearing Janie’s voice, her love, and her pain.

Hurston refused to separate her identities as anthropologist and storyteller. In fact, she grew up in Eatonville, and likely modelled many of the characters' voices on people she knew intimately. She recognised that fiction could convey truths about cultural experience that academic writing often missed or sanitised. By allowing her characters to speak in their own voices and navigate their own complex social worlds, she created what might be considered one of the first major examples of narrative ethnography.3

But as well as blending fiction and ethnography, Hurston often drew on her own experiences. As mentioned, she grew up in Eatonville. She also married three times in her life. Perhaps this is why though the book details the sad facts of Janie’s experiences, the affective substance is joyful: Janie is always appreciating the beauty of life, and Hurston reflects that beauty in her prose. The result might be some kind of fictional autoethnographic, or fictive ethnographic autobiography. Whatever the term, the book speaks for itself.

Today, anthropologists increasingly recognise the value of interdisciplinary approaches. Hurston's work stands as a powerful reminder that sometimes the most effective way to document a culture is through its stories. As we continue to grapple with questions of voice, authenticity, and representation in both literature and anthropology, Hurston's work reminds us that sometimes the most illuminating path lies somewhere between objective observation and subjective storytelling—in that liminal space where ethnography meets fiction. Her choice to merge anthropology and fiction ultimately created a living, breathing portrait of a community in all its complexity, beauty, and contradiction. And one that has stood the test of time, and which has ultimately been recognised for its importance.

If you liked what you read, or you want to see more from An Elsewhere Anthropologist, please consider subscribing. If you’re already a subscriber, please consider sharing this post. Every bit helps!

Schmidt, Nancy J. 1984. “Ethnographic Fiction: Anthropology's Hidden Literary Style” Anthropology and Humanism 9(4): 11–14.

Dolan, Michael. 2024. The American Porch: An Informal History of an Informal Place. Open Road Media.

There were definitely earlier ethnographic fiction texts, but few have achieved such broad significance as this one.