New and Future Chimeras

A Bestiary of the Anthropocene, Cataloguing the Hybrid Creatures of Our Making

Bestiaries as Moral Guides

Among the most beautiful and horrifying of all historic texts might be the bestiaries of the Middle Ages. Beautiful because they were some of the most carefully and imaginatively illuminated manuscripts. Horrifying because of the frightening creatures that dwelled within their pages. These books listed creatures known to prowl the Earth, whether real or mythical – the boundaries then were less defined, the categories still nascent. In their pages one might find themselves attacked by the explosive diarrhoea of the bonnacon, or the deadly unicorn-like monoceros.

The bestiaries were not simply beautiful catalogues of nature. They were a sort of guide through the moral landscape. A reflection of the beliefs and worldviews of the time – where one could safely be, and where one could not. It was not all about monsters, though. The Northumberland Bestiary, previously the Alnwick Bestiary, included poetic instruction for clergymen to avoid the temptations of women.

These texts, rather than being the work of any individual, are thought to have been produced by workshops of artists and scribes. But the books are a collective project in another sense: the beasts in their pages were often taken from other bestiaries, or travellers accounts, word of mouth, and maps. At the edges of maps, as the refrain goes, there be monsters.

Liminal Spaces

Monsters exist in liminal spaces – the boundaries beyond familiar territories and known rules. An explanation might suggest that monsters populated the extreme limits because these were territories that had not yet been explored, and to fill blank spaces in knowledge and on paper, cartographers and explorers would let their imaginations roam. Or perhaps they would hear – or make up – stories of the vicious barbarians on the other side of the border, an "Other" so vicious at the gates of civilisation that they took on monstrous proportions. But liminality offers another view.

Popularised by the anthropologist Victor Turner in the 1960s and 70s, the term ‘liminal’ relates to a process in ritual where a person moves from the known, ordinary world, through a liminal “in-between” space, into the heightened or altered state of ritual. Within this liminal space, we bypass known categories into the unknown; meanings are often inverted or altered and the ordinary rules do not apply. Turner states:

Liminal entities are neither here nor there; they are betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention, and ceremonial. As such, their ambiguous and indeterminate attributes are expressed by a rich variety of symbols in the many societies that ritualize social and cultural transitions.1

Liminality helps us understand a couple of things about monsters and bestiaries. Firstly, its worth noting the very word "monster" shares its Latin root (monstrum) with "demonstrate" — something shown or revealed, often as a divine warning. Monsters demonstrate the boundaries of the known world, the thresholds beyond which lays darkness and the unknown. Spatial limits become synonymous with moral ones.

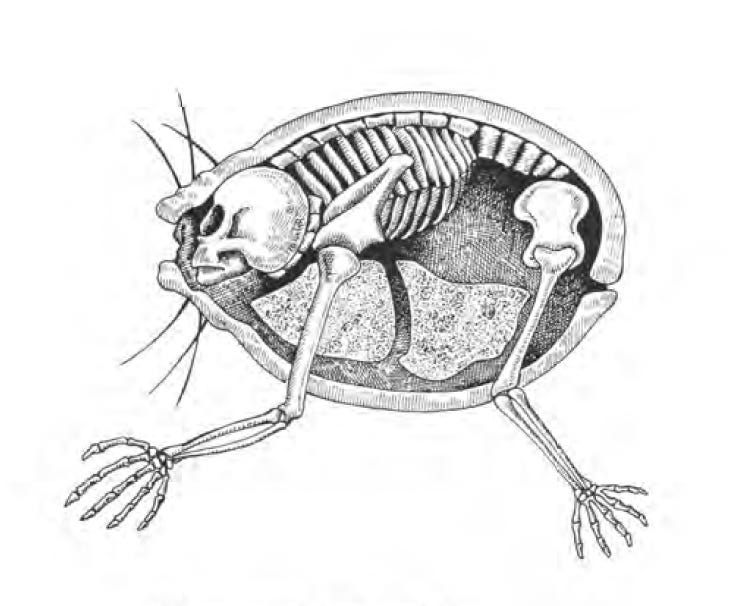

Liminality also helps us to understand why monsters in bestiaries are often admixtures of catalogues, since in liminal spaces normal categories don’t apply. A monster is often a creation when you mix two different things within one category (a gryphon, for example, mixes a lion with an eagle), or when you cross two things from totally different categories, such as animal and human (think centaurs or Jeff Goldblum as the Fly), human and technology (cyborgs), the living and the dead (zombies and vampires) and so on. These creatures are monstrous because they emerge from a liminal place where the ordinary rules do not apply; we don’t understand them because they don’t follow the rules.

But what liminality shows us is that in such places, creativity dwells. When the ordinary rules don’t apply, new things may emerge. The realms of imagination may be considered such liminal spaces; untethered by the demands of physics and biology, the mind can take us to strange places and imagine new creatures, new places, new futures.

Bestiary of the Anthropocene

We now live in an age where the hallmarks of human habitation on Earth will continue long after our disappearance. The World Without Us, by Alan Weisman, is a form of speculative non-fiction. He poses the question: What would happen to our human-centred planet if humans vanished tomorrow? He then meticulously details various things that would quickly vanish, and other things that would be around for thousands of years to come. How long does it take before our homes are fully reclaimed by the natural environment? How long does our waste remain as evidence of our habitation? If we disappeared tomorrow and never produced another plastic bag or toothbrush again, fish will still be eating our plastic for thousands of years to come.

As we become increasingly aware that we are now in the Anthropocene – our current geological age defined by humanity's profound impact on Earth's systems – I find myself drawn to a modern reimagining of the bestiary form to make sense of the limits of this new world. What creatures populate its extremes? How might we catalog the hybrid entities emerging at the intersections of nature and technology?

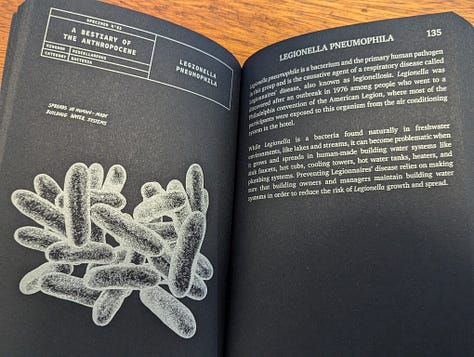

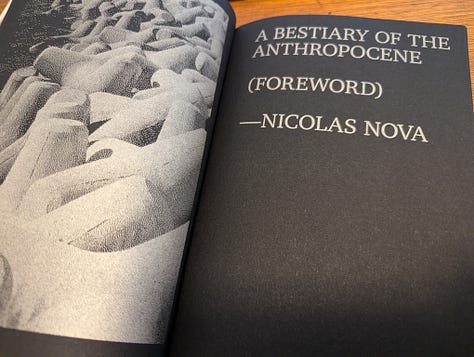

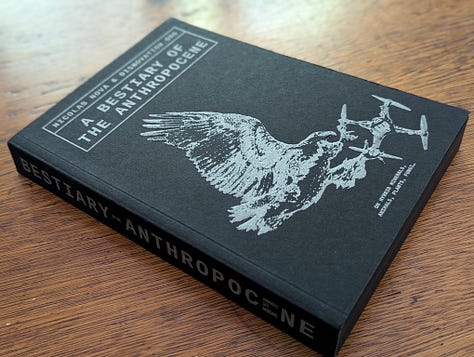

A Bestiary of the Anthropocene offers compelling answers. Produced by Nicolas Nova and disnovation.org, I picked up this dark, gorgeous book at the Iceland Art Book Fair in 2024. Much like medieval bestiaries divided creatures into kingdoms of land animals, birds, serpents, and sea organisms, Nova categorises his specimens into kingdoms of minerals, animals, plants, and miscellaneous matters.

Consider the "plastiglomerate" — neither fully stone nor plastic, but a new hybrid material formed when discarded plastics melt and fuse with beach sediment, shells, and organic debris. Or the similar "fordite," a layered material formed from accumulated automobile paint in factories. Or chicken bones, which have become so ubiquitous thanks to industrial farming that they now constitute a defining feature of our geological epoch. These are just three markers of the mineral deposits of the Anthropocene; there are 60 such entries in this bestiary.

The book doesn’t only document mineral hybrids but technological modifications as well. There are entries for surveillance robot dogs, cell phone towers disguised as trees, and genetically modified organisms. Some entries depict the unintended consequences of our technologies — strangled turtles deformed by plastic rings, or hermit crabs that mistake bottle caps for shells, becoming trapped and starving. Others highlight intentional creations, like dolphins trained to track vessels, or eagles trained to intercept unauthorised drones.

Two things strike me about this bestiary. The first is how it captures a pivotal moment in Earth's history – the merging of the biosphere and technosphere into one hybrid ecosystem. Just as medieval bestiaries helped their readers navigate and make sense of their world through symbolic creatures, Nova's book offers us a field guide to this transformed planet. It also raises the question of whether the division between "natural" and "artificial" as we so commonly imagine it is less definite than we might have thought. Just as "real" and "mythical" were combined in medieval texts, so too are contemporary categories fused.

The second is that many of the creations and hybrids in this bestiary are not out there in the margins and peripheries, but in our very homes and most intimate spaces. True, we might never encounter a militarily dolphin trained to track ships at sea. But the biomass of all the chickens made for food consumption now exceeds the biomass of all other birds on the planet, just so you and I can have a fillet in the fridge or pick up a convenient bucket of fried wings. These hybrids are proliferating not only in the margins but everywhere, and often without our notice.

Speculative zoology

Another response to our human-centred and human-altered world would be to imagine the strange hybrids it may someday produce, as well as considering those it already has. Here, speculative zoology and speculative anthropology might be worth a moment’s reflection.

The self-proclaimed "father" of speculative zoology is Dougal Dixon. After Man: A Zoology of the Future imagined what direction evolution might take animals into an imagined future era. A follow-up book, Man After Man: An Anthropology of the Future, imagined what the future might hold for humanity after thousands of years of changing environment and genetic engineering.

Dixon's work represents a modern bestiary of sorts, one rooted in scientific principles and speculation rather than moral instruction. The illustrations of strange future creatures create a menagerie every bit as fantastic – and at times horrific – as medieval bestiaries, yet grounded in evolutionary possibility. What makes Dixon's work so compelling is not just scientific attention to ecological niches and anatomical adaptations, but the willingness to use wild flourishes of imagination to both convey these evolutionary forces and speculate on the future of the world. By moving into the speculative space, Dixon allows himself the freedom to imagine, and in doing so answer difficult questions.

Dixon's work has spawned an entire genre of speculative evolution. Contemporary speculative zoologists create detailed taxonomies of creatures that might evolve on Earth after human extinction or on alien worlds with different environmental conditions. Online communities like the Speculative Evolution Forum showcase thousands of imagined creatures with detailed anatomical drawings and ecological contexts. This modern bestiary movement exists in its own liminal space – between science and fiction, between academic exercise and artistic expression. They remind us that the strange creatures of our planet's past and the potential creatures of Earth's future may be every bit as alien and fantastic as anything imagined in ancient texts.

In a world increasingly concerned with extinction and biodiversity loss, these speculative zoology projects serve another purpose – they invite us to imagine futures where life continues to adapt and thrive, even if in forms we might find unrecognisable from our current perspective. They challenge our anthropocentric view of the world and remind us that life's story extends far beyond humanity's chapter.

Where Dwell the New and Future Chimeras?

Medieval bestiaries helped their readers navigate both geographical and moral landscapes, marking boundaries between the known and unknown, the safe and dangerous. Our modern bestiaries serve a similar purpose, though the monsters they catalog no longer dwell at the edges of our maps but within our everyday: our homes, our very bodies. The chicken bones in our trash, the microplastics in our blood, the cell towers disguised as trees along our highways — these are the new chimeras of our age, hybrids that demonstrate the inextricable entanglement of the natural and the artificial.

In this sense, the Anthropocene might seem to have eliminated the liminal zone that once separated human civilisation from nature. There is no longer an "out there", where the monsters dwell; the monsters are here, often of our own creation, proliferating in plain sight. In truth, this division between nature and culture was always only a mirage, a means for us to assert our own desires on the world around us. The bestiary itself is an effort to catagorise that which seems is beyond catagorisation. As with a cartographer who maps new territories, the effort to make a catalogue is the effort to control that which you include in it: to make it known, quantified, described, understood, and exploited.

Maybe the effort to categorise in modern times, as with A Bestiary of the Anthropocene, is an effort to make us all aware of our own impacts on the environment and, therefore, to help us limit those impacts. Rather than allow these hybrids to proliferate freely, perhaps we might stop and consider precisely what we wish to leave behind.

We still need symbolic vocabularies, creative imaginaries, and even moral frameworks to help navigate these new terrains. This is where speculation becomes a useful tool. The consequences of past transgressions was once to be attacked by hybrid monsters out in the wild margins of the world. Today, they’re in our homes. But foreseeing these consequences requires imaginative, creative speculation, as we see with speculative zoology and other such creations.

Liminal spaces are perhaps best suited for this reimagining. Creative spaces, however we interpret this idea, are the most exciting, most productive when they exist somehow between or beyond the bounds of the ordinary. Arts residencies are so often ‘out there’ in nature for precisely this reason, so that the creative practitioner can escape the bonds of mundanity. Squats and arts communes often exist on the fringes of legality, outside ordinary behaviour. In liminal spaces, we’re free to test the limits of what seems possible and imagine a world remade.

We must bend and break the rules as they appear to us and occupy these liminal spaces. Imagine new ways of being and living. Take care and pay attention to the inversions so that the norms are made all the clearer. This is where creative speculation, fiction, and anthropology overlap: they each have the powerful capacity to make the strange familiar and the familiar strange. Like the scribes of old, we need to document and interpret these new creatures, not just as scientific curiosities but as signposts guiding us through the strange landscape we've created for ourselves. And we need to imagine new paths, new lands, new futures.

Suggested Reading

Historical Bestiaries & Their Context

Morrison, E. & Grollemond, L. (2019). Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World. Getty Publications.

Camille, M. (1992). Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art. Harvard University Press.

Modern Bestiaries & Speculative Zoology

Nova, Nicolas & disnovation.org (2021). A Bestiary of the Anthropocene: On Hybrid Minerals, Animals, Plants, Fungi… Set Margins’.

Dixon, D. (1981). After Man: A Zoology of the Future. St. Martin's Press.

Dixon, D. (1990). Man After Man: An Anthropology of the Future. St. Martin's Press.

Naish, D., Kosemen, C.M., & Conway, J. (2012). All Yesterdays: Unique and Speculative Views of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Animals. Irregular Books.

Anthropocene & Environmental Studies

Weisman, A. (2007). The World Without Us. Thomas Dunne Books.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Bonneuil, C. & Fressoz, J.B. (2016). The Shock of the Anthropocene: The Earth, History and Us. Verso Books.

Tsing, A., Swanson, H., Gan, E., & Bubandt, N. (Eds.) (2017). Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene. University of Minnesota Press.

On Liminality & Monsters

Turner, V. (1969). The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Cornell University Press.

Asma, S.T. (2009). On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears. Oxford University Press.

Cohen, J.J. (Ed.) (1996). Monster Theory: Reading Culture. University of Minnesota Press.

Musharbash, Y. & Presterudstuen, G.H. (2020). Ethnographic Explorations of Transforming Social Worlds Through Monsters. Routledge.

Visual Resources

Serafini, L. (1981). Codex Seraphinianus. Franco Maria Ricci.

Riera, L. & Tite, J. (2019). Extinct: An Illustrated Exploration of Animals That Have Disappeared. Phaidon Press.

What Is An Elsewhere Anthropologist?

Join me in cataloguing the wonders and warnings of our changing world, to explore the edges of our maps where new monsters demonstrate the consequences of our actions and imagine different possibilities for coexistence in this hybrid landscape we now inhabit.

These occasional posts explore the intersections of anthropology, speculation, fiction, and the weird and wonderful world.

Welcome to An Elsewhere Anthropologist.

Field Note #452

Included with each post is a field note from elsewhere: a fictional vignette about something that might be real.

My guide was showing me the fallow cornfields when I saw it. Something I’d only ever heard of, but had never seen. A Pollin.Ai. It was dead, or whatever you call a non-functional entoborg. My guide explained that almost all the natural and industrial beehives had collapsed over a decade ago – as they had in most other places. Serious ecological collapse was averted when the government reluctantly agreed to sign contracts with the developers of these semi-artificial pollinators.

Modelled off the original DragonflEye, produced by Draper Laboratory back in 2017,2 these insects were genetically modified to be receptive to steering and control commands wired directly into their nervous systems. Control systems did not even require human input: they were entirely managed by AI-generated models for optimal pollination. This particular brand, the Pollin.Ai, was the product of local companies that imitated the original patents without proper licensing, much to the impotent fury of the owners of the IP in their distant corporate towers. For the first few years, these creations seemed to be the saviour of the local economy, but with subsequent wetware updates the code slowly degenerated, left to the AI for self repair.

There were “incidents”. Two years ago, a swarm stripped four square kilometres of fields, bankrupting local farmers. In another case, an introduced weed that had almost been totally eradicated became the focus of the Pollin.Ai model, and almost overnight the pest was again thriving across the region. A third incident saw the insects become weird cannibalistic monstrosities, stripping themselves and each other of parts and recombine them into displays of strange artistry that only an AI glitchmind could concoct.

Then there were the claims that Pollin.Ai was using its insects not only to farm corn, but data. The locals called the insects ‘agents’, of the government, the corporation, or both – that depended on who you asked. Any time someone swatted at a fly or heard the high drone of a mosquito, they acted as though they were being watched. That is to say, they almost always acted as though they were being watched.

This particular insect I found looked like a hybrid of a bee and a dragonfly, with a long narrow abdomen. Its chitinous shell shone in bands of black and yellow; the black bands were strips of solar microdots to power the circuitry. The little cyborg’s legs still twitched in a suggestion of agony, though this might just have been the dying electrodes jolting the body with their final volts. One wing had been badly damaged.

“The birds attack them,” my guide explained. “They sometimes choke on the components, or they fill their stomachs.”

Excited by this discovery, I reached into my bag to pull out a clean pair of socks. I planned to wrap it carefully and take it home with me.

“Don’t,” my guide warned. “The licensing laws are strict. You could be arrested.” She explained that all of the entoborgs one sees populating the fields and skies were owned by Pollin.Ai, and even taking a dead sample was considered theft.

“But they’re faulty. They’ve stripped your fields of corn,” I say, confused.

“Yes. But it’s better not to get their lawyers involved, too,” she said. “They’ll take much more than our fields.”

And so I sketched this little thing, just as botanists and entomologists once sketched the fragile wings of the now extinct Apiformes.

Other notes

If you’re interested, I am a student anthropologist and an emerging author. I have a number of other projects going on – specific to anthropology, to my writing, and other hybrids of the two. Check out my website for full details.

My latest blog post is about a queer magical realist novella I’m writing called Live With Me, Sorrow.

You can sign up for my general author updates on Substack below. Or you can follow me on Instagram, Bluesky and Mastadon.

And to finish up, it helps hugely to share what you’ve read with anyone you think might enjoy it. Please consider doing so.

Thanks for reading.

Turner, V. 2010. ‘Liminality and Communitas’ in Ritual. Routledge, p. 359. Originally from Turner, V. 1969. ‘Liminality and Communitas’ in The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Aldine Publishing.

Nova, N. & disnovation.org (2021). A Bestiary of the Anthropocene. Set Margins’, p. 91.