Dancing with Ghosts

Field Observations from the Backrooms

It starts with a song. One that sounds a little familiar. You've heard it somewhere before, maybe. Or you feel you might have, in some distant past. It echoes through the corridors of memory. It warbles with distortion, like an old gramophone has been warped by time. It flickers like candlelight.

This is how I first encountered the Backrooms. Not with a photo, but with music.

[Go on. Listen while reading…]

The first piece I heard was "It's just a burning memory", by The Caretaker, followed then by the rest of the album, Everywhere at the End of Time (2016). The image that occurred to me as I first listened was very specific: walking through the corridors of a grandiose but decaying old theatre or hotel and coming upon a ballroom in which were forever dancing the spirits of the dead.

This conjures a further recollection in me. For many years the White Bay Power Station was closed and bordered up, gathering dust in the Sydney suburb of Rozelle. We would pass it on our drives into Sydney from the Western Suburbs and as a child I wondered what it was like inside. Before it was refurbished into a cultural centre and reopened, I was fortunate enough to go on a tour inside the building. And inside, a derelict ballroom at the top of this power station, designed in the modernist fashion to bring workers together to create a sense of community.

This could easily have been the ballroom of my imagination, both in its hay-day and in its dilapidation.

If you're not aware, Everywhere is just one album in a series spanning twenty years by musician The Caretaker (aka James Leyland Kirby). I can't recall, when I first heard the album, if the ballroom image was one I was already primed for in reading about it, or if the image did genuinely come to me from the music alone. I mention this because the first few albums in the series are called the Haunted Ballroom Trilogy, which started in 1999. This was followed by the Amnesia period, and finally the Everywhere at the End of Time series, which was completed in 2019.

The original concept was inspired by a similarly haunted ballroom at the Overlook Hotel in The Shining (1980). While the early albums evoke nostalgia, with warbling old tunes distorted into horror-scapes, later albums explore the descent into dementia. Music flutters in and out of sequence, fading and phasing into something else. Something broken. And eventually, silence. I've often thought that if there are ghosts, it is not they who haunt us but we who haunt them. If this is the case, The Caretaker's series tracks that process musically from haunting through to forgetting and, finally, death.

The whole experience taps into something unspoken and unspeakable: that haunted part of the mind where nostalgia, fear, and the many things we'd rather not think about all seem to dwell. These are the backrooms.

Where are the backrooms?

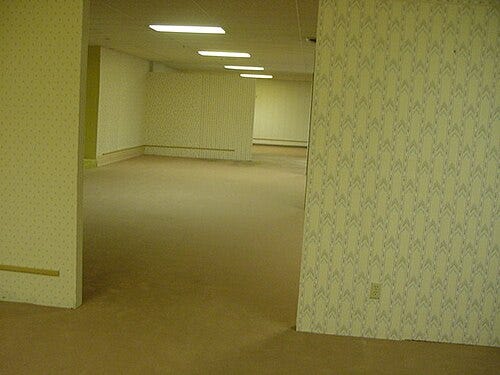

The concept of the backrooms is usually linked to a 2008 image posted on 4chan, an early creepypasta meme that has spread into a whole horror sub-genre.

For the uninitiated, creepypasta is a kind of internet folklore, a term used to describe horror content that is generated and shared online (Slender Man is a common and famous example). Like the backrooms themselves, the term creepypasta is taken from 4chan. Originally, the term 'copypasta' (copy + paste) was used on the forum to describe blocks of text that were commonly copied and shared. This portmanteau was again adapted for copied and shared stories with a creepy element (creepy + copypasta = creepypasta).

In a message board prompting users to provide a 'normal' image that was somehow unnerving, one user posted an photo of an office room captured through a doorway. The bright overhead lighting, off-putting yellow pallor, the weirdly mismatched wallpapers, the dirty carpets, the windowlessness, the tilt of the frame – all of it combines to give a sense of unease. The photo came with this message:

If you're not careful and you noclip out of reality in the wrong areas, you'll end up in the backrooms, where it's nothing but the stink of old moist carpet, the madness of mono-yellow, the endless background noise of flourescent lights at maximum hum-buzz, and approximately six hundred million square miles of randomly segmented empty rooms to be trapped in.

God help you if you hear something wandering around nearby, because it sure as hell heard you.

Pulling back the veil slightly, the image itself was taken from a website of the Hobbytown store in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. The store was conducting a refit of their basement rooms to build them into an indoor racing space and posting on their site about the process (full photoset is available here).

"Noclip" refers to a command in video games used to turn off collisions, allowing the player to move through walls and floors, into spaces they were never meant to see.

These elements combined into what was perhaps part of the inspiration of the fourth-wall breaking video game, The Stanley Parable.

In the Stanley Parable, you play Stanley, employee 427 in a large and unpopulated office building. When your computer stops working, you decide to explore the office. Your actions are pre-narrated by an authoritative voice, but it's up to you to decide whether you comply with the narration or go your own way. At times, the narrator – exasperated with the choices of the player – will speak to you directly, bringing you into the game world. In this sense, the game itself is a sort of liminal space between reality and the strange, empty corridors and office rooms portrayed on screen.

The game has multiple endings and in at least one play-through, you end up walking 'above' the game space looking down on it from above in an imitation of no-clipping through the walls. In multiple ways you're moving between spaces, or rather, from 'ordinary' game space into liminal space.

Places betwixt and between

There's a word anthropologists use for the spaces between spaces: liminal, from the Latin limen, meaning threshold. Victor Turner called them places "betwixt and between" – neither here nor there, but elsewhere. Think of often-romanticised twilight, that transition between day and night. That's a liminal moment.

Another anthropologist, Arnold van Gennep, coined the term in his book Rites de Passage. Rites of passage are those ceremonies that mark the great transitions: birth, coming of age, marriage, death. In some cultures, for example, to become an adult a child must first be ritually killed, so that they might be reborn into adulthood. The person who enters the ritual is not the same one who emerges. In between, they exist in a suspended state, no longer who they were, not yet who they will become.

A liminal space is one in which the ordinary rules do not apply. Social norms and identities are inverted or reframed. What is known to be true might no longer be, at least for a time. When the individual returns to the collective, they return not as they were but as something new. Changed.

The backrooms are a kind of contemporary mythic liminal space, both recognisably belonging to our world and yet also otherwise. They are both familiar and strange. To enter them subverts spaces so familiar to many of us (office workplaces) so that they are re-presented in ways that seem peculiar or otherwordly. The backrooms are an example of the familiar uncanny.

Endless corridors and familiar uncanny

From the architectural historian and critic Anthony Vidler we get the concept of the 'familiar uncanny', which describes a place that should be familiar to us but which is somehow made strange. I remember as a student walking through the grounds of my school at night, when no-one else was around and many of the lights were off – a familiar place was rendered both strange and unnerving. Or visiting my home town after many years, only to find some things were the same and others completely different. We perceive the world to be safe and familiar. The familiar uncanny reveals the frailty of that perception.

These places are unnerving because they suggest a loss of rational control. What we know to be the case is revealed as only a veil of perception; things can be otherwise. The size of the Backrooms – so unfathomably large and full of unknown lurkers – are suggestive of the edges of the maps, where monsters dwell. The mundanity of the office space is inverted, taken to extremes. Expanded into six hundred million square miles, we feel trapped in the vastness.

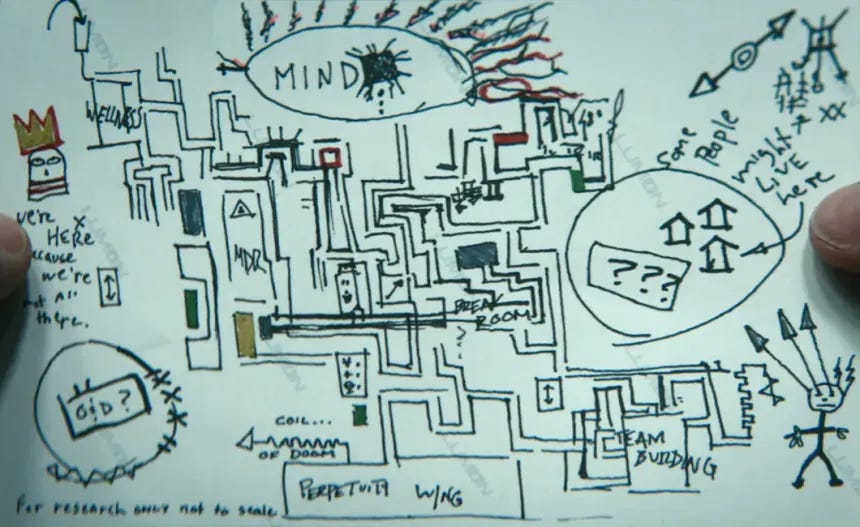

Here it's perhaps useful to think of poor Mark Scout (played by Adam Scott) in Apple TV's Severence (2022–). Constantly walking down seemingly never-ending corridors, dehumanising in their clinical whiteness, their rigid straight lines suggesting conformity and boredom. And yet, from above, they appear to be nothing less than a chaotic mess, a maze either designed to madden the rats inside or designed by a mad architect. These spaces are made uncanny – dreamlike – in repetition, scale, unnatural simplicity, and so on. The corridors of the Severed floor are also a liminal space, where everyday workers are removed from the ordinary rules of society and made into something new; only, this liminal space is wrapped up in corporate jargon and capitalist exploitation. The employees in *Severence* do quintessentially *bullshit jobs*, as anthropologist David Graeber decribed them: pointless, lacking in broader social value, causing psychological harm, defensive in their roles despite their pointlessness.

The Backrooms play off a kind of deep-seated disquiet about modern architectural environments. Office spaces are not natural; they're a kind of social engineering we willingly participate in each day. The idea of the endless office space is just an extension on the cubicle farms and corporate campuses that have come to represent the modern workplace in people's minds. These spaces, designed for efficiency, control, and surveillance often feel deeply alienating to their human occupants. In the photo of the Backrooms (imitated in the Stanley Parable, made clinically white fluorescent light in Severence) the yellow walls, mismatched wallpaper, stained carpeting, all gave an impression of a space that was both contemporary and always already in a state of becoming dated, of dying, or of decay.

The colour also reminds me of 'The Yellow Wallpaper', a short story by Charlotte Perkins Gilman published in 1892, in which a woman is confined to a room in her home to recover from some illness. But the confinement and the disturbing yellow wallpaper only exacerbate her sense of unease, until at last she is driven mad by it. Of course referencing the suffocating conditions of the women of her time, the same metaphor of confinement and unease is at work in the backrooms.

But there's something else lurking in those yellow walls – not just present suffering, but the ghosts of promises that were never kept.

Haunted by empty spaces

This brings me to hauntology. The term ‘hauntology’ comes from philosopher and social theorist Jacques Derrida as a portmanteau of haunting and ontology. Nothing in the past is ever merely in the past. It haunts our present, our reality in ways that impact us all the time. I think about the decisions that lead us to wherever we now are. Not just personal ones, though those matter too (the career paths not taken, the relationships that slipped away), but the larger promises that shape entire generations. The post-war dream of endless progress. The idea that technology would liberate us from drudgery. The belief that each generation would live better than the last. Decisions made in families, communities, even governments have consequences that echo through history. These decisions haunt us, whether we know it or not. All presence is haunted by absence: what is missing, what was promised but never delivered, what might have been, and what was but no longer is.

(A whole spin-off to this discussion is alternate histories, or ‘sliding-door’ style stories, where the game is to imagine what might have been, if only…)

The Backrooms phenomenon emerged during a period of increasing awareness about the psychological costs of late capitalism. Young people faced a world where traditional markers of adulthood like stable employment, homeownership, starting a family, all seemed increasingly out of reach or cause for stress and anxiety.

In the endless corridors of the Backrooms, we are haunted by the spectre of meaningless work. They are build for productivity and yet they are always empty: empty of purpose, empty of meaning, empty of people and human relationships.

The Backrooms are also a kind of hauntology because they harken back to the optimistic modernism of the generations before. The offices of Severance, for example, have an anachronistic feel in the design of technology, colour palette, office paraphernalia. There's a vaguely 60s and 70s vibe. This place-out-of-time feel suggests that these spaces once stood for progress, opportunity, and advancement. Now, they are unstuck in time. Neither fully present nor past. Decaying. They are, in short, haunted by a future that never materialised: the hope and promise of meaningful lives full of abundance, where progress would lead to improvements in people's lives.

Dancing at the end of time

This all brings me back to the Caretaker's albums echoing through the corridors of recollection. The Caretaker albums aren't merely taking hauntology as an aesthetic gimmick. Those warped gramophone melodies suggest a time and place where memories become corrupted, looped, and which gradually fall into silence, suggesting the decay inherent in life.

Cultural critic Mark Fisher understood something crucial about The Caretaker's project that goes beyond aesthetic experimentation. In Ghosts of My Life, Fisher argues that we live in a culture trapped in what he called "hauntological time" – where the future has been cancelled and we're left endlessly recycling the past. The Caretaker's twenty-year journey from nostalgic ballroom melodies to complete dissolution maps this cultural predicament. As the series progresses into the abyss of dementia, we're not just witnessing individual memory collapse, but the slow-motion breakdown of collective memory itself. The final stages of Everywhere, where melody dissolves into static and silence, is like the suffocating sense that this is all there is, that no alternatives are possible. In those last, wordless tracks, we hear what Fisher called the "No Wave" of our historical moment: not just the end of a mind, but the end of the very possibility of imagining different futures.

The spirits I imagined dancing in that ballroom are not only ghosts of the past. They are ghosts of futures that never came to pass, trapped in the backrooms of our world, in what remains of once-optimistic visions of the future. Trapped not in ruins, exactly, but spaces caught between what was promised and what was delivered. The spirits are also our futures, for we, too, may end up dancing in degrading loops, awash in our own frail and dementing memories.

Textual references

If you like some of these ideas, check out the following:

Music

The Caretaker, or James Leyland Kirby here.

The Backrooms OST, by Iwakura:

Bohren & Der Club of Gore

Films and TV

The Shining (1980), dir. Stanley Kubrik

Memento (2000), dir. Christopher Nolan

Severence (2022–), dir. Ben Stiller

Mulholland Drive (2001), dir. David Lynch

Tales from the Loop (2022), dir. Nathaniel Halpern

Books, Games, Other Media

'The Yellow Wallpaper' (1892), by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Download here.

Ice (1967), by Anna Kavan. Here.

Annihilation (2014), by Jeff Vandermeer. Here.

The Stanley Parable (2013). Here.

Control (2019). Here.

Theory

Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life (2014)

David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs (2018)

Victor Turner, The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual (1967)

Arnold van Gennep, Rites de Passage (1909)

Anthony Vidler, Warped Space: Art, Architecture, and Anxiety in Modern Culture (2000)

Got other suggestions for texts? Or thoughts about this post? Let me know.

Not already subscribed? Here’s a conveniently located button.

Loved what you read? Share the love!

Had this one sitting on my e-mail for over a month now. Glad I waited until i could sit and read relaxed, great writing! And also reminded me of a couple of things I wanted to look into and had been lost to my own backrooms, namely finishing Control and checking of Stanley Parable lol